How do we treat unique talents?

Hi everyone,

This is a minimally edited repost of something that was previously part of the paid subscribers only archive that I liked enough that I wanted it to be broadly available. It was originally published in May 2021. If you were a paid subscriber before I discontinued paid subscriptions, you’ve probably already read it then, sorry.

People are complicated, and I think about this a lot. I’m especially interested in individual variation, and the people who violate our norms about how humans “should” be and how we treat them. Today I’d like to talk about three examples of that.

Not one of us

Let me start by telling you a story.

It’s not a story about me, I promise, except to the degree it’s about everyone. You’ve almost certainly heard it before, but possibly not told quite in this way.

The story starts with an abused child.

The child was not abused by his parents, as far as we know. His parents are absent from the story. Perhaps he was an orphan, or perhaps they were simply indifferent to his plight. Perhaps they cared, but didn’t know what to do. Whatever the reason, the outcome was the same.

The child was abused by his peers. They bullied him, taunted him, excluded him from their social activities. They made it very clear that he was not one of them, worthless to them.

Why?

Well because he was different. He stood out from the crowd, unable to pretend to be like everyone else. He wasn’t doing anything that harmed them with his difference, he was just unable to conform to their idea of what a child should be, and they hated him for it.

The child’s story gets happier, a little.

You see, his difference was also a talent. It was useful. It let him do things that the other children could not.

He could not take advantage of this on his own, but fortunately an authority figure noticed him. A powerful man found his talent, decided that it was exactly what was needed for his ends, and nurtured him in it.

This stamp of approval was enough to grant the child some respite. Now that his abnormalities had been deemed acceptable, and now that he had a powerful protector, the other children tolerated him. They ceased their bullying, and included him, and he grew up to be a valued and productive member of society.

This is where the story as it is told ends, but I can’t help but wonder about some of the details.

Did the other children really include him? Or did they just pay lip service to the idea? Certainly they would not be so foolish as to bully the star in ways that they could get caught. My guess is that they got good at subtle jabs that made it clear that he was tolerated but not accepted.

Certainly many of them would be looking for the moment when he was no longer in favour. His inclusion was granted. He was not included for himself, but because someone above him had granted him that right. Even that authority figure did not value him for himself - not truly - only for what he could do.

And what about when he encountered others not subject to that authority? Would they treat him well, or as he had historically been treated? Would his peers defend him, or would they be happy that he was being reminded of the conditionality of his inclusion? Let others say what they could not?

I also wonder about his future. At some point in the far future he will retire, no longer useful. Or perhaps he will decide to set out on his own, taking advantage of the skills and resources has earned from his service to authority. What then? Will he still be “loved” now that he is no longer useful to his benefactor?

Anyway, as you can tell, I think about the story of Rudolph the Red-Nosed Reindeer a lot.

The man who loved people and also numbers

I’ve recently been reading about Paul Erdős, and apparently the gold standard for learning about him is the book “The Man Who Loved Only Numbers”.

I am glad I read this book, but I wish there were a book that was like it but good. I believe that the author had good intentions, but honestly I do not think he treated his subject very well.

In particular, I had not realised until I came to write this entry quite how much I hated the title.

Here are some excerpts from the book.

In 1971, Erdős's mother died of a bleeding ulcer in Calgary, Canada, where Erdős was giving a lecture. Apparently, she had been misdiagnosed, and otherwise her life might have been saved.

Soon afterward Erdős started taking a lot of pills, first antidepressants and then amphetamines.

As one of Hungary's leading scientists, he had no trouble getting sympathetic Hungarian doctors to prescribe drugs. “I was very depressed,” Erdős said, “and Paul Turin, an old friend, reminded me, ‘A strong fortress is our mathematics.’”

Erdős took the advice to heart and started putting in nineteen-hour days, churning out papers that would change the course of mathematical history. Still, math proved more of a sieve than a fortress. Never again could he bring himself to sleep in the apartment that he and his mother shared in Budapest; he used it only to house visitors and moved into a guest suite at the Hungarian Academy of Sciences.

For the rest of his life he'd bring his mother up at odd moments. "I was walking across a courtyard to breakfast at a conference," recalled Herb Wilf, a combinatorialist at the University of Pennsylvania, "and Erdős, who had just had breakfast, was walking in the opposite direction. When our paths crossed, I offered my customary greeting, ‘Good morning, Paul. How are you today?’. He stopped dead in his tracks. Out of respect and deference, I stopped too. We just stood there silently. He was taking my question very seriously, giving it the same consideration he would if I had asked him about the asymptotics of partition theory. His whole life was spent thinking hard about serious mathematical questions, and he treated this one no differently. Finally, after much reflection, he said: ‘Herbert, today I am very sad.’ And I said, ‘I am sorry to hear that. Why are you sad, Paul?’ He said, ‘I am sad because I miss my mother. She is dead, you know.’ I said, ‘I know that, Paul. I know her death was very sad for you and for many of us, too. But wasn't that about five years ago?’ He said, ‘Yes, it was. But I miss her very much.’ We stood there silently for a few awkward moments and then went our separate ways."

It wasn’t just his mother. He was very fond of children:

His memory for children rivaled his memory for mathematics. "When he asked a father of four, “How are the epsilons?”, it did not mean that he did not remember the names of the children. Just on the contrary - he perfectly well knew the names, ages, past illnesses," and other significant events of those children and "a few thousand others," said Pelikan, now a graph theorist at Eotvos Lorand University in Budapest.

(“epsilons” was part of his odd personal language, it means children)

And the vulnerable:

Erdős also forged a special bond with anyone he perceived as vulnerable. In 1945, when Michael Golomb was in Philadelphia at the Franklin Institute doing war service for the government, he got a call from Erdős, who was passing through town and wanted to get together. Golomb explained that he was going to a party that evening at the home of a fellow mathematician who was eager to meet Erdos and would be happy if he showed up. Erdos did come to the party, but instead of conversing with the mathematicians he promptly disappeared. "We did not see him for the rest of the evening," Golomb recalled. "Only when everyone was ready to leave did we learn that Erdos had found out that our host had a blind father, who could not join the party, but sat up in a room on the upper floor. Erdos preferred spending the time with the lonely blind man rather than with the people in the party, who were eager to meet him."

Erdős by the very account of the book was full of love for others, to the point where the title seems an almost intolerable insult to me (I do not know how it was picked - this may not be the author’s fault. Authors often don’t have full control over titles).

A better title might be “The man who was loved only for numbers”.

The above may make Erdős sound like a saint, and perhaps in some ways he was, but honestly Erdős sounds almost intolerable. He was a demanding house guest, argumentative, and generally incredibly difficult to deal with.

Here is a representative example of what Erdős was like as a houseguest:

We used to leave coffee and cereal out for him because he'd get up earlier than us. One day when I came down to the kitchen there was cereal, lots of cereal, all over the floor. I didn't understand how it got there. Even if he opened a new box and had to struggle to rip the plastic, that much cereal couldn't have shot out. I couldn't figure it out, so I just swept it up. The next morning I came down and there was cereal all over the floor again. Erdős was sitting there, dropping fistfuls of cereal, trying to feed the dogs."

Erdős was hard on everyone's floors. "Paul liked to wash his hands all the time," recalled Dick Schelp. "He really had this thing about picking up germs. You'd leave out a fresh towel but he wouldn't use it. He'd just shake the water off. My son said that after he's been in the bathroom, it's like walking in the middle of a swimming pool. There's water all over."

At least water can be cleaned up. Some Uncle Paul sitters, though, were not as lucky. "He was staying in one of our kids' bedrooms," said Plummer. "He had various skin afflictions and brought with him different wet and dry substances, different lotions and powders, to put on himself depending upon how his skin felt. He had taken a bath and his skin bothered him. He wasn't sure which substances would help, so he had lathered himself with lotion and talc. He managed to spill the lotion and talc all over the floor. He tracked footprints across the bedroom. The prints are still there!"

He also seems fairly difficult to deal with in professional contexts:

Vazsonyi told Erdős about the Monty Hall dilemma. "I told Erdős that the answer was to switch," said Vazsonyi, "and fully expected to move to the next subject. But Erdős, to my surprise, said, 'No, that is impossible. It should make no difference.' At this point I was sorry I brought up the problem, because it was my experience that people get excited and emotional about the answer, and I end up with an unpleasant situation. But there was no way to bow out, so I showed him the decision tree solution I used in my undergraduate Quantitative Techniques of Management course." Vazsonyi wrote out a "decision tree," not unlike the table of possible outcomes that vos Savant had written out, but this did not convince him. "It was hopeless," Vazsonyi said. "I told this to Erdos and walked away. An hour later he came back to me really irritated. 'You are not telling me why to switch,' he said. 'What is the matter with you?' I said I was sorry, but that I didn't really know why and that only the decision tree analysis convinced me. He got even more upset." Vazsonyi had seen this reaction before, in his students, but he hardly expected it from the most prolific mathematician of the twentieth century.

Or the following story from Ronald Graham about Paul Erdős’s interactions with Fan Chung (another mathematician and also Graham’s wife):

"When he didn't understand something," said Graham, "he did not make it easy for you to convince him. He was always interrupting and getting angry. Conversely, when he tried to explain a proof to you, it was not always easy to follow him. Once Fan was so annoyed with him that she said she was never going to work with him again. I was al ways the intermediary between the two of them, part translator, part peacemaker. Paul left out a lot of mental steps when he was explaining something. If you were with him a lot, you could stop him and make him fill them in. Fan does the same thing when she explains something, only she leaves out different steps. So when they're communicating back and forth, they're leaving out too many steps. Paul had a problem he really cared about and Fan solved it. He asked her to explain the solution. She had barely started when he suggested another approach. She said, ‘No, Paul, I'm explaining this.’ Finally after half an hour she was completely frustrated. And he said, ‘I don't think Fan's English is good enough to explain this to me.’

That sent her over the edge because her English is perfectly good. Paul just wanted to see it in his way. When you've thought about a complicated argument and you have your own notation in your mind, and Paul interrupts and says, ‘Well, try it this other way and define such-and-such as the inverse,’ it's like asking a right-handed person to do a difficult new athletic stunt left-handed. ‘What? I can barely do it right-handed.’

Erdős seems lovely in some ways but also just incredibly difficult to deal with.

Part of this is that he was probably extremely autistic. He was never diagnosed - I don’t know if the idea even occurred to people at the time - but it seems like a hard conclusion to escape, and he fits the pattern, up to and including his physical mannerisms:

"Erdős is somewhat below medium height, an extremely nervous and agitated person ... almost constantly jumping up and down or flapping his arms. His eyes indicated he was always thinking about mathematics, a process interrupted only by his rather pessimistic statements on world affairs, politics, or human affairs in general, which he viewed darkly. If some amusing thought occurred to him, he would jump up, flap his hands, and sit down again."

There’s a wide range of behaviour in autistic people of course, but Erdős’s pattern of behaviour makes much more sense coming from an autistic person than someone more neurotypical.

So why did people put up with Erdős given his general difficulties? Was it just because he was nice to small children and the vulnerable?

No, it was because he was one of the greatest mathematical geniuses of the 20th century, by any reasonable measure. Importantly, he was not only a genius, but he was really good at collaborating with others. Erdős was not a solitary genius, he was a prolific collaborator.

The cost of interacting with Erdős might have been high, but the benefit was that you got to work with Erdős. For many mathematicians, this was obviously a good trade.

You think you’re worth that?

Erdős reminds me a lot of Richard Stallman, and one of the things I kept thinking while reading this book was that it was probably a blessing that Erdős lived before the internet, and especially Twitter, took off in a big way, because the discourse around him would have been absolutely awful, largely based on having watched how it treated Richard Stallman, especially historically.

Richard Stallman is a prominent figure in the software world, and the original advocate for the Free Software movement. He has a, mostly deserved, reputation for being extremely difficult, but for better or for worse the modern software world would look utterly different than it does without his advocacy efforts.

There are a lot of legitimate things you can say against Stallman, and I’m personally very much not a fan, but most of the things people have actually said about Richard Stallman over the years are pretty far from legitimate and sure seem like it’s because he’s weird and as such an easy target.

A rather central example of this sort of commentary around him is discussion about his conference rider. His conference rider has a lot of fairly strong demands, some of them genuinely quite onerous. For example he wants veto power over any other speakers at the same event as him. I personally don’t think this is unreasonable (especially given the speaking fees he could be commanding and as far as I can tell mostly isn’t), but that’s not what the discussion focuses on. What the discussion actually focuses on is how weird people think some of his requests are.

This discussion on Hacker News is fairly representative of the genre.

heyrhett

All of his demands are either directly related to his health or the moral causes that he champions. He is specific and verbose.

Some of these things might seem strange to people who are younger than 50 years old, and aren't flown around the world to give hundreds of talks.

I think that this demonstrates the value of a clear and verbose contract.tibbon

Precisely. Nothing is left to ambiguity, and then hopefully the fewest possible things will go wrong.

About the only thing that I laughed at (in joy) was the thing about parrots...stickfigure

Nothing is left to ambiguity?

A supply of tea with milk and sugar would be nice. If it is tea I really like, I like it without milk and sugar. With milk and sugar, any kind of tea is fine. I always bring tea bags with me, so if we use my tea bags, I will certainly like that tea without milk or sugar.

Really, I think he's just screwing with us. Douglas Adams would be proud.derleth

How is that even somewhat ambiguous? Personal and, perhaps, skirting the outer edge of what a remarkably parochial person might regard as quirky, but he laid out a drink preference specific enough someone has a shopping list and doesn't have to guess. Which is what a rider is for.

You don't even need to buy him tea; he explicitly says he always brings his own with him.hugh3

So if I provide tea he likes, I don't have to provide milk and sugar. If I provide tea he doesn't like, I have to provide milk and sugar. Unless of course he chooses to drink his own tea, in which case my tea, my milk, and my sugar will all go to waste.

This is fine, as long as I know precisely what kind of tea he likes. But that's not specified, so I just gotta guess what he might like. And then buy some milk and sugar, just in case he likes my fancy tea just enough to drink it, but not enough to skip the milk and sugar.

Really I think he's just writing his opinions on tea off the top of his head.smacktoward

Having had experience organizing lots of public speaking/platform events, I can assure you that "please provide milk and sugar" is one of the easiest-to-comply with requests I've ever seen. He doesn't specify that it must be soy milk, or 2%, or half and half. He doesn't say it has to be natural cane sugar grown on the sunny side of a hill and harvested by certified sugar cane naturalists during the summer solstice. He just wants milk and sugar; beyond that he leaves the details to you.

Worst case scenario is that he doesn't use them, in which case you're out what, two dollars? That is peanuts compared to what some riders cost you by specifying elaborate A/V and lighting setups, specific vendors and contractors (i.e. friends of the speaker) you have to deal with, luxury transportation and lodging, et al.

As to the "what kind of tea" issue, he helpfully solves the problem for you -- he'll bring his own, which he is guaranteed to like. So there's no scenario where your failure to choose the right tea will result in him being tealess. Strictly speaking the only thing you're on the hook to provide is hot water, which is free and easy to scrounge up at short notice.

It's really a remarkably stress-free document, as riders go.Samuel_Michon

It would've helped if he had just specified which kind of tea he likes. That way, he wouldn't have needed to write most of that paragraph.

Now we're left to guess, which means we will stock several kinds of tea, in the hopes of one being to his liking.smacktoward

Several kinds of tea?!? Oh no, anything but that.wnight

Or, not, because he hasn't asked for it.

He's basically saying, "if you provide tea provide a full tea service or I likely won't like it." If you don't want to provide that, don't.

If that's too complicated he repeatedly says "email me and ask". "Hey RMS, what tea would you like us to buy" would do it. As would giving him $0.75 for the tea bags he brought, if you feel the need.

It's so low maintenance.

The parrot thing is from his pets section of his rider:

I like cats if they are friendly, but they are not good for me; I am somewhat allergic to them. This allergy makes my face itch and my eyes water. So the bed, and the room I will usually be staying in, need to be clean of cat hair. However, it is no problem if there is a cat elsewhere in the house--I might even enjoy it if the cat is

friendly.Dogs that bark angrily and/or jump up on me frighten me, unless they are small and cannot reach much above my knees. But if they only bark or jump when we enter the house, I can cope, as long as you hold the dog away from me at that time. Aside from that issue, I'm ok with dogs.

If you can find a host for me that has a friendly parrot, I will be very very glad. If you can find someone who has a friendly parrot I can visit with, that will be nice too.

DON'T buy a parrot figuring that it will be a fun surprise for me. To acquire a parrot is a major decision: it is likely to outlive you. If you don't know how to treat the parrot, it could be emotionally scarred and spend many decades feeling frightened and unhappy. If you buy a captured wild parrot, you will promote a cruel and devastating practice, and the parrot will be emotionally scarred before you get it. Meeting that sad animal is not an agreeable surprise.

People often comment on this section as weird, and it’s certainly a little unusual, but it honestly seems like a perfectly sensible set of considerations to me (the “don’t buy a parrot” thing is a bit odd, but it does sounds a bit like the sort of thing people would do. Possibly there’s a story there, possibly he’s just being overly conscientious).

I think, often, what’s actually going on, is that people who are not directly getting the benefits of RMS are engaged in perfectly standard punish-the-weirdo norm policing. RMS has this rider precisely because he is in demand - people want RMS to speak at a lot of things, so he's able to ask for things in exchange. He could almost certainly demand very high speaking fees - I don’t know what fees he gets, but the rider doesn’t make it sound high and suggests he’s often speaking for expenses only. If he were to behave in a way people deemed perfectly respectable and charge a $10,000 speaker fee, he’d probably get much less flak, but because he tells you he likes parrots he triggers the punish-the-weirdo norms.

You can see that this is going on with how ridiculous some of the complaints are. As smacktoward puts it, “Several kinds of tea?!? Oh no, anything but that”. People aren’t objecting to Stallman because of any actual objections to his behaviour here, they’re reacting to the fact that he’s being odd, and will weaponise anything no matter how innocuous in order to do that.

The people who are actually used to him, or indeed to other eccentric conference speakers, just mostly take it in stride, because they’re the people who are actually getting to make the cost-benefit analyses.

Exploiting deviation from the norm

A previous piece of mine that I end up thinking about a lot is The Usefulness of Bad People, about how we let other people do necessary evils so that we can judge them for it while also reaping the benefits of their actions. e.g. I use the example of people who become social nexuses precisely because they’re slightly bad at boundaries.

The way we interact with such people is a fascinating exercise in doublethink. “Yes, it’s good that you do these useful things”, we ask, “but couldn’t you do them while also being a good person?”

And the answer is no, they could not, because the thing that makes them useful to us is precisely the thing that causes us to judge them as bad. Achieving the desired outcome ethically is hard, and few people are managing it, so we instead free ride off the bad behaviour of others and judge them for it to feel better about ourselves.

I feel like at a broader level we do the same with the weird. We’ve constructed a civilisation which is happy to take advantage of individual oddities, but is unwilling to support them, and barely willing to tolerate them.

And yet, the things that we are taking advantage of are precisely the things we are punishing. Could Erdős have been Erdős without his overriding obsessions? Perhaps one could have softened his rough edges without detracting from his genius, I don’t know, but I cannot help but feel that it would have been hard for him to have had the impact he did while living any sort of “normal” life.

The situation is even worse for those whose obsessions are not deemed useful. Erdős “got away” with being who he was because interacting with him was so unambiguously worth it. What if it hadn’t been?

Erdős was loved by many, and not all of that love was conditional on his genius, but I think it’s important to acknowledge that without his genius he would not have been so loved. It opened doors, and created space in which people could get to know him. How much worse would his life have been without that?

When I first published this I finished with the following:

I feel like I have much more to say on this subject, but my thoughts here are still a bit chaotic and half formed, so I’m going to end this piece somewhat abruptly, and instead of a satisfying conclusion I will leave you with this meme.

My thoughts these days are still a bit chaotic and half formed, although they’re now a larger chaotic and half-formed morass that I’m sure I can extract something more meaningful to say about this, but I’ll leave that for another time.

Share the news!

If you liked this issue, you are welcome and encouraged to forward it to your friends, or share it on your favourite social media site:

If you’re one of those friends it’s been forwarded to or shared with and are reading this, I hope you enjoyed it, and encourage you to subscribe to get more of it!

Community

If you’d like to hang out with the sort of people who read this sort of piece, you can join us in the Overthinking Everything discord by clicking this invitation link. You can also read more about it in our community guide first if you like.

Additionally, by being part of the community you get the uh privilege of seeing these posts when they’re much worse, as I tend to post first drafts there. Thanks to everyone there for reading a first draft of this post and helping me improve it.

Other writing

I’m trying to do more writing on my consulting site, so here’s an article I wrote recently: Quick fixes to your code review workflow. It’s pretty much what it sounds like - easy interventions to common problems with code review. If you don’t know what code review is, don’t worry about it this article isn’t useful to you.

I’m also declaring draft bankruptcy and going through some unfinished newsletter drafts which I’ll never finish and posting the good bits of them to my notebook. So far I’ve posted:

There will probably be daily posts there for the next week or so.

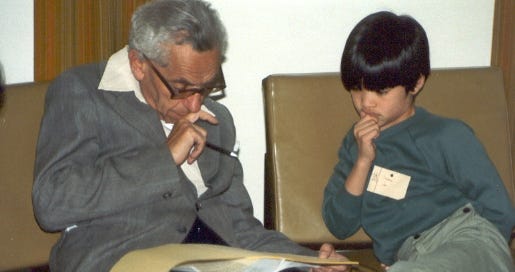

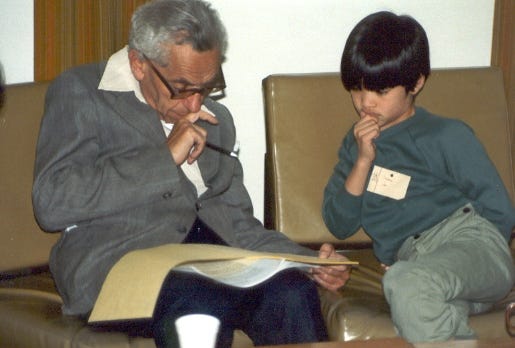

Cover image

The cover image is Paul Erdos with a young Terence Tao, obtained from wikimedia commons.