Hi everyone,

This is the weekly free issue of “Overthinking Everything” which goes out every Wednesday. There is also a paid issue every Sunday. The last one was Understanding your health is hard, which explored the large gap between what we can know for certain to be true and where we have to just make our best guess, and how much of our experience of our health and how to improve it lives in that space.

Today I’d like to talk to you about small insights, and how they can unblock us from tasks that seem intractably hard.

How to open those stupid stitched bags

You know those stupid stitched bags that you get some things in (big sacks of rice and potatoes mostly for me, but they’re used for other things too).

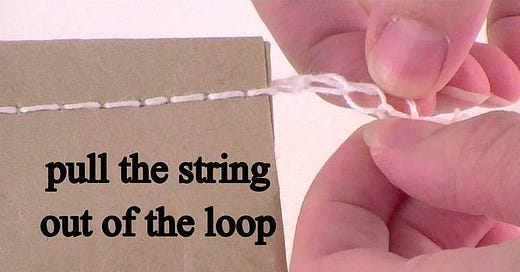

Do you know how to open them or do you always make a total mess of it like me? If the latter, here, watch this video:

If you can’t be bothered to watch the video, the key insight is this: You need to untie the end, and then you can just pull the two pieces of string and it easily comes apart. No need for scissors, no mess, it’s easy.

(I didn’t actually watch more than about 30 seconds of the above video myself, because she went “You need to untie the string” and I went “Oh” and then I tried opening the sack of potatoes I had just bought and it immediately came apart when I did that step first).

Probably you already knew this. I don’t actually know what the distribution of this particular bit of knowledge is. My guess is that well over 50%, probably more like 90%, of people who have ever had this problem know how to solve it, but I didn’t, and when I tweeted about it neither did a number of others. I expect enough people read this newsletter by now that this will also be news to a handful of you.

The thing is, the world is full of these ridiculous mundane pieces of insight, and even if you’re very on the ball and know 99% of the ones that would be life improving for you to know, that probably still means that there are thousands you are missing.

YouTube is pretty good for this, and keeps getting better every year. If there’s something that you feel stupid about, you can probably just search YouTube and you’ll find a bunch of videos telling you how to do it.

Many of them are bad, but that’s OK. You can skip around in the video, and you can watch it on double speed, and you should get a pretty sense of whether it’s good or bad and whether you need to watch it in more detail or whether you’ve got the insight already.

How to clean your bathroom floor

As you may have noticed a recurring theme of this newsletter is that I’m not very good at cleaning. I’m not awful at cleaning - I’m not living in filth or anything - but my flat is permanently slightly messier and less clean than I’d like.

One particular eye sore is that my bathroom floor is often a bit gross. I’m not very good at mopping, to the point where I rarely mop because even after mopping the floor just doesn’t look clean and the whole thing is unpleasant and aversive as a result because I know I’m going to put in a bunch of work and then still feel like an idiot afterwards because surely mopping is easy, right? What kind of idiot is bad at mopping?

Anyway I decided to finally follow my above advice and look up a YouTube video on how to mop. It turns out I’m fine at mopping. The instructions on how to mop are basically what I was already doing. I watched a couple videos, increasingly confused.

Then I watched one that gave me the key insight.

So, uh, did you know you have to sweep or vacuum before you mop? Because I sure didn’t. I think in my head there were rooms that you mopped and rooms that you vacuumed, and never the twain shall meet. This is not the case. You need to get the debris off the floor before mopping

I can’t say my bathroom floor is immaculate right now - I still don’t like cleaning very much - but it’s a hell of a lot better after taking the vacuum to it than it ever was after mopping.

I was getting very frustrated because the mop was not picking up debris. It is, in retrospect, entirely obvious that this is not what mops do, but I had thought that the reason the mop wasn’t doing it was that I was bad at mopping, so it never occurred to me that I might be doing the wrong thing rather than doing the thing wrong.

How to use a search engine

A thing that is less true these days now that Google tries to be basically magic, but is still worth bearing in mind (especially for site specific search engines that aren’t Google) is that the way to search for something is to enter a term that is likely to be true of the things you want and false of the things you don’t want. e.g. an unusual word or phrase that is likely to be included in the document.

You also need to try multiple searches. Often the first search or two you find won’t work. That’s OK.

Often you should combine multiple attributes to search on. For example, if you’re looking for a paper and too many generic things are coming up in Google scholar, try finding a paper it’s likely to cite and search within its citations. If you’re looking for a tweet, see if you can remember who it might have been from (or to!) and do a from:username or to:username query.

But really the single most important way to learn to use a search engine is this: Know people who are better at using search engines than you, and when you get stuck ask them for help and ask them to explain what they did and why they did it, and remember that for next time.

How to catch a ball

Sometimes the insight is more experiential than a straightforward sentence, such as when I learned to catch a ball at age 36.

My Alexander Technique teacher just casually taught me how. It’s a little hard to describe the key insight there without sounding like a platitude, but basically the key is to not try to focus too much on how you are moving and to focus more on what you’re trying to do. It helps to distract your conscious mind a bit - he did it by having a conversation with me and telling me to focus on him rather than on the ball.

Here’s another Alexander Technique insight:

“Jared,” I said, “Let’s try something different. It’s very simple. Stand at the plate and hold the bat the way you usually do. I’m going to throw the ball, but I don’t want you to move your bat. Leave it where it is. Tell yourself not to swing. All I want you to do is watch the ball as it moves toward you. Keep watching the ball as it approaches you, as it crosses the plate, and even as it passes by you. See it the entire time it’s moving. You don’t have to do anything else. Got it?”

“Okay,” he answered. In a single word Jared’s voice expressed a mound of doubt. I ignored him and pitched. After the ball passed by him, I asked if he’d seen it the entire time that it was in the air.

“I think so,” he answered.

“Let’s try it again.”

I pitched. “What about this time? Did you see the ball the entire time it was moving?”

“That’s weird.”

“What’s weird?”

“I saw the ball as it was coming toward me, but when it was about three feet in front of me it sort of disappeared. Then I saw it again after it passed by me. That’s really weird. How’d that happen?”

While Jared was feeling puzzled, I was feeling hopeful. If he could perceive that he had stopped seeing the ball, we had something I could work with—an experience that might cause him to change his belief.

“That’s great. You’re starting to know what it means to see the ball. You have to see it clearly during the entire time that it’s traveling toward you. When it sort of disappears like that, it means you’ve stopped seeing it. When you tell me you’re not sure if you saw the ball that means you didn’t really see it. Want to try this again?”

(From How you stand, How you move, How you live, by Missy Vineyard, in Chapter 13)

“You have to actually look at the ball to hit it” is a pretty obvious insight, but sometimes it requires someone walking you through the process of what looking at the ball is actually like.

How to ping somebody

I’m somewhat on the fence about whether Lambda School itself is good or bad (I’m aware that being on the fence about something like this is a good way to make both sides hate me, but nevertheless), but I think this interview with the Lambda School founder, Austin Allred, is very good.

I’m particularly a fan of this section:

There was this other time I was in college…I was hustling and trying to get into startups and there was this guy at a conference I wanted to work with, so I went up and talked to him. And I said what can I do to be like you? He gave me his business card and said just ping me next week.

I spent hours and hours and hours looking up what ping me meant. I couldn't find anything. So eventually I called somebody and said hey, this guy said ping me. What does that mean? How do I ping? And that person was like, no, no, it’s a call or an email or anything really, just reach out to them. Doesn’t matter how. That's all that ping means. You know, like a cell tower. Ping! I was like, ohhhhhhhh! There's so much little stuff like that. Another classic example is intros, right? Or using Google Calendar. I didn't know how to use Google Calendar until I showed up in my first job. Someone tells me, I am gonna put some time on your calendar. And I think: Oh, I guess I have a calendar. That's not obvious if you don't come from, frankly, a certain class. But all of those things are important; if you don't intro somebody the right way to a VC, they know you're a dunce, automatically. There’s nobody that sits you down and says hey, you're gonna say thank you so-and-so, moving you to BCC. It's not hard, but nobody ever tells you that anywhere.

As I said, the world is full of these ridiculous mundane pieces of insight, and most people to whom they are relevant have most of them, but importantly these insights are not evenly distributed. If you are coming into a situation with a radically different background than most people in that situation, you will be disproportionately short of them.

How to prove a theorem

If you’re struggling with proofs, try learning sudoku first and then transferring the lessons from how to prove that a given square must contain a given number back to more general proof.

How to play sudoku

(Please note that I am no more than OK at sudoku)

The way to be good at sudoku is essentially to learn a bunch of systematic procedures and results which you can just try in order, and then to gradually get an intuitive sense as to what a sensible order to try them in is.

Your basic procedure is that for any square you can try to narrow it down by writing down all numbers that it could be, crossing off anything that is ruled out, and if you rule out all but one number write that down definitively in that square.

If you just apply this rule to each square in turn, starting again from the beginning when you get to the end if you’ve successfully filled in one square, you will complete a lot (by no means all) of beginner puzzles.

After that you need to learn more complex patterns. For example naked pairs let you identify which numbers are in a pair of squares, but not which is which, and this can let you rule out those numbers appearing elsewhere, which can in turn narrow things down.

Learning to be good at Sudoku is a mix of acquiring many individually small insights and a lot of intuition as to which order to apply them in, and this protocol of “Learn a brute force method, acquire intuition as to how to speed it up, and apply it until you get stuck then figure out a new insight” will serve you in good stead in many other areas.

How to pass as “normal”

One of the reasons I get quite grumpy about the quality of mathematics education is that we’re very bad at teaching the insights bit. We just show people a bunch of mathematics and hope they figure the insights out on their own.

We utterly fail to teach all the implicit mundane insights that occur along the way of getting good at mathematics, and mathematics is something we’re trying to teach. It’s part of the “explicit curriculum”. But there’s also the hidden curriculum:

A hidden curriculum is a set of lessons "which are learned but not openly intended" to be taught in school such as the norms, values, and beliefs conveyed in both the classroom and social environment.

Any type of learning experience may include unintended lessons; however, the concept of a hidden curriculum often refers to knowledge gained specifically in primary and secondary school settings, usually with a negative connotation. In these scenarios, the school strives for equal intellectual development between its students (as a positive goal), and the hidden curriculum refers to the reinforcement of existing social inequalities through the education of students according to their class and social status. The distribution of knowledge among students is mirrored by the unequal distribution of cultural capital.…

The term "hidden curriculum" also refers to the set of social norms and skills that autistic people have to learn explicitly, but that neurotypical people learn automatically.

I don’t actually know how much of this is literally an autism problem and how much of it is being the “weird kid”. I’m not autistic (probably), but I definitely experienced a similar problem and had to learn a lot of the hidden curriculum in my 20s and 30s. There are all sorts of things you learn from your peers that you won’t have access to if your peers treat you as the weird outsider (see How to be weird).

I know someone on Twitter who has a child didn’t know how to interact with other people, so she went and read every self help book in the library. This actually seems very reasonable to me and I wish I’d thought of it at the time.

Reading books usually won’t teach you the hidden curriculum, any more than you can learn to dance from a book, but it will give you a reasonable pool of insights to try on and see what happens, and it will help you navigate the world a bit better without getting stuck.

I think better even than books is a friend who is slightly (not too much!) better at this than you are, so you can ask them stupid questions, and ask them how you come across to others.

This is sometimes a bit of a bootstrapping problem, I admit.

How to improve your writing

Read it out loud and listen to how it sounds. If that doesn’t work, try reading it out loud and imagine it’s being said by someone who you find slightly irritating. What stands out as the thing you would pick on?

How to generate novel ideas

Try writing down a list. Pick the size of the list in advance to be larger than you think you can manage. 30 is a good number.

How to solve your problem

Explain it to a rubber duck, or other suitable toy with a face.

How to get better at everything

If you’d asked me six months ago how to get better at something, I’d probably have pointed you to how to do hard things. I still think this is a good approach and you should do it, but I now think it’s the wrong starting point and I’ve been undervaluing small insights.

Often when you’re stuck on how to get better at something the answer really is to treat it as a skill that you can get better at through careful work and practice, but you may also just be missing an insight, because skills are build around thousands upon thousands of small insights.

Also, the relative impact of learning a new insight that gets you unstuck is so much greater than that of a lot of training, because it can instantly get you unstuck, so the cost is so much lower. This often makes it worth it in contexts where a more laborious process of skill development is not.

Consider our starting example. Imagine spending time learning how to open stitched bags. Is it worth an hour of training in some fiddly technique that you have to keep in practice on? Probably not - in any context where you have to open enough of these bags that that would be worth it, you’re just going to use scissors to cut open the bag. Is it worth 5 minutes on YouTube to learn the trick? Yeah, absolutely.

So I think my revised belief is that if you are stuck at how to get better at something, spend a little while assuming there’s just some trick to it you’ve missed. You can try to generate the trick yourself, but it’s probably easier to learn it by observing someone else being good at the thing, asking them some questions, and seeing if you have any lightbulb moment.

Coaching Auction

Every week I auction off a coaching session based around the Wednesday free newsletter issue. We spend an hour talking about something loosely based on the theme of the issue and discussing relevant ways you can use it to improve your life. You can bid for this week’s coaching session here.

The auction uses a mechanism called a Vickrey auction, where you submit a sealed bid, and the winning bid pays the price of the second highest bid (so you never pay more than you bid, but will always pay less unless there is a tie, in which case you pay the amount that you bid). Last week’s Life is a Series of Events, the winning bid was £59, paying £50.25.

In addition, although I’m not currently taking on new recurring coaching clients, I do offer one off sessions, currently at £95 for an hour session, so if there is some problem on your mind that you think I could help you with (anything from feelings to software development), feel free to drop me an email at david@drmaciver.com to enquire.

thank you so much, this helped me so much today. I can't thank you enough for writing and sharing with us

love this