A good start

A student and a master were walking back from the market when they saw a beggar by the road.

The master reached into the basket the student was carrying, took out some fruit, and handed it to the beggar. The beggar thanked the master graciously, and they moved on.

After some time, the student asked the master. “Master, why did you give fruit to that beggar?”

“Because he was hungry.”

“Ah, and you wished to embody the virtue of generosity?”

The master gave the student a look.

“No, I gave the beggar fruit because he was hungry.”

“Why must we then give all such hungry beggars fruit?”

The master sighed in exasperation.

“Why must I answer all such questions?”

The student had no answer to this.

They walked in silence for a while, until they passed another beggar. Unprompted, the student gave the beggar some fruit. The beggar thanked the student graciously, and they moved on.

After some time, the master asked the student. “Student, why did you give fruit to that beggar?”

The student began to answer, and then paused to consider so as to answer honestly. Eventually the true words came.

“I believed that you would think well of me for doing so.”

The master smiled appreciatively and nodded. “It’s a good start.”

They walked in silence for a little while longer before a thought seemed to occur to the master.

“Of course, now we shall have to do without dessert tonight.”

In that moment, the student did not become enlightened, but it was a good start.

The many paths to wisdom

A student came to the master.

“Master, I have learned many things. I have learned the humble arts - I can cook, and I can clean. I am well versed in the fine arts, I can draw and I can write. I understand the sciences, and have plumbed the deeper mysteries of how the trees grow and the stars form. I have honed my body, I can fight and I can run. I have mastered all of these things, but I am not yet wise. What must I do?”

The master responded thus: “Wisdom lies in knowing what to do. With each new skill you have mastered, you have made wisdom harder, for there are so many more things that you can do. When there is but one path before you, you have all the wisdom you need to walk it. When there are thousands of paths, great wisdom is required to decide among them. You have learned many paths, now you must learn to choose among them.”

The student bowed to the master and left.

Some time later, the student returned.

“Master, I have studied right action, and many thousands of the paths available to me. I have learned what to do on each. Am I now wise?”

The master responded thus: “You have studied thousands of paths, but how many paths are available to you?”

“Master, the paths are numberless.”

“And having studied thousands among numberless paths, do you now know what to do?”

The student bowed to the master and left.

Later, at dinner, the student spoke once again to the master.

“Master, consider this bowl of rice. It has thousands of grains in it, each different. And yet I know how to eat them all. I have eaten hundreds of bowls of rice like it, each bowl with a different number of grains, in a different configuration, and yet I have known how to eat them all. Why are paths then different? Although there be numberless paths, need I learn each path individually, or are they more like bowls of rice where knowing one is sufficient to know the others?”

The master picked up a handful of dried rice and poured it in a line upon the table.

“There are many grains of rice in this line, and yet there is only one path.”

The student bowed, and dinner continued in silence.

The next day the student came to the master.

“I understand now. There are not numberless paths, but instead only one path: The one I choose to walk.”

The master smiled.

“That is entirely wrong, but perhaps you should behave as if it were true for a while and see how it goes.”

In that moment, the student did not become enlightened, but they did begin to walk the path.

Which way should I go?

The student came to the master.

“Would you tell me, please, which way I ought to go from here?”

“That depends a good deal on where you want to get to,” said the master.

“I don’t much care where—” said the student.

“Then it doesn’t matter which way you go,” said the master.

“—so long as I get somewhere,” the student added as an explanation.

“Oh, you’re sure to do that,” said the master, “if only you walk long enough.”

In that moment, the student felt the master was being singularly unhelpful.1

Practical wisdom

The student came to the master.

The master spoke thus: “Go away, I’m busy.”

“But master, I have come a long way seeking your wisdom.”

With a long suffering sigh, the master emerged from beneath the engine of the car they were repairing.

“Oh, it’s one of you. Go on then, what do you want?”

“Master, I have heard you possess great wisdom.”

The master grunted, grudgingly conceding that this might be the case.

“I wish to know what I should do with my life.”

The master rolled their eyes at the student.

“You should pass me that wrench.”

In that moment, the student passed the master a wrench.

Postscript

Having recently declared draft bankruptcy, I consider myself free of all prior obligations on things to write on the newsletter, and as such have a bit more room to experiment. So I shall be experimenting. Some of it might even make sense. If you want to see (incomplete) pieces in the previous style, all of the abandoned drafts have been posted over on the notebook.

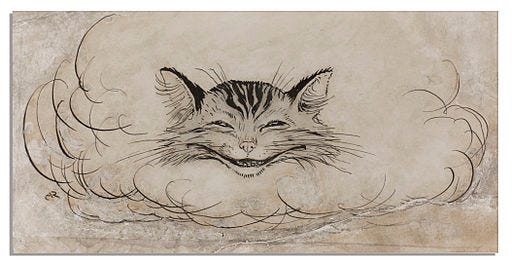

The cover image for this piece is Arthur Rackham’s drawing of the Cheshire Cat.

With apologies/credit to Lewis Carroll.