Describing imaginary experiences

Hi everyone,

I was talking to Lucy yesterday about visualisation, and about our parallel experiments to improve our abilities at it.

She introduced me to Image Streaming a while back, a practice that is supposed to improve your ability to visualise. I find it eminently plausible that it would work, and I absolutely hate doing it for reasons I don’t fully understand, so I’ve been trying a variety of idiosyncratic methods of my own and generally trying to understand the problem better. Still, Image Streaming seems to be producing interesting results for her.

As part of my attempts to understand and improve on this, what I’ve been trying to do is pay attention more to the things that are like visualisation that I can do, and to try to notice the subjective experience of them and improve upon them.

Anyway, apparently this results in me being doomed to my usual fate of being the one to have to explain things that I only understand because I’m bad at them, as Lucy reports that my explanations of how things worked were among the clearest she’d been able to find. So here is my attempt to explain visualisation to you, speaking entirely from the perspective of someone who can barely do it.

Language without shared objects

One of the big difficulties with describing subjective experiences is that there are no shared objects. With things in the external world, you can just point to it and say “You see that thing? That’s an apple.” and then through a process of trial and error and talking about it you can come up with a reasonable working language for distinguishing apples from non-apples.

As well as objects, this is also how we learn more general descriptive words like colours. A mini version of the problem with describing subjective experiences is the common question “Do we mean the same thing by red?”. i.e. is the red I see the same as the red you see? I’ve never found this question very interesting to try to answer, because the notion of “red” is for coordinating external experiences. What matters is whether we agree on what things are red,1 not whether our subjective experience of that redness is the same.

With fully internal experiences, you don’t have these shared objects to use as references, and are generally reduced to metaphor and analogy to shared objects, and it can be very hard to adequately convey them. For example, how do you describe a headache? You can say that it hurts (we have plenty of shared experiences of things that hurt), you can describe where it hurts. You might be able to say that it’s a stabbing pain, or that it’s pulsing, or that you feel tense in particular areas, but speaking as something of a connoisseur of headaches this is far from a complete description of the experience, and relies heavily on external analogies (we know what a stabbing pain is like because we know what it’s like to get stabbed) or very general properties (location, time variance, etc).

And this is a very clear, universal, experience. Everyone2 has headaches and this is how bad we are at describing them.

There are plenty of experiences that are less shared and correspondingly harder to describe. For example I have a recurring experience where the best I can describe it is something like… being hyperaware of my skin and the blood beneath it and feeling like it’s full of static. That’s the best I can do to explain it. It’s something I get when I wake up after a bad night’s sleep sometimes. It’s not tingling, it’s not itching, it’s not painful, but it’s intense and unpleasant.3

Generally I don’t even try, I just tell people “Imagine I wake up hung over most mornings”, because that brings us back into the realm of shared experiences (more or less. Is my hangover actually the same as your hangover? We can’t easily say, but it doesn’t really matter - we know how to interact with hungover people, and that’s not dependent on the internal experience being the same.

As your subjective experiences get weirder, you lose access to even that common understanding of how to behave, and this problem gets more acute. Eventually your metaphors get outlandish enough that people think you’re insane. For example, there’s Cotard’s delusion, in which people “think” they’re dead, or that a limb is dead, or missing, or alien, etc. Matthew Ratcliffe’s book, “Feelings of Being”, explores this and other delusions and argues pretty convincingly that they mostly don’t represent literal false beliefs, but are instead an attempt to communicate a genuinely strange subjective experience that they have no other means of communicating but metaphor.

My most “insane” subjective experience like this is that I have a strong muscle memory of how to fly, probably acquired during flying dreams. I can’t actually fly, I’m very clear on this, but at some bodily level it’s weird that I can’t just push off the ground and into the air. There’s a lot of random variation in subjective experience that goes like this (I know other people who have similar experiences, though their internal conception of how to fly seems different from my own), and people mostly just don’t notice because they don’t talk about it, and thus when you run into an experience that is different enough that it’s important to talk about, that experience seems weirder and more delusional than it actually is.

Treating these variations as delusions is like a diagnosis of “phantom pain” - when you go to a doctor and they tell you that nothing is wrong and the pain is all in your head. That may be so, but you are still in pain, and it is that experience you trying to understand and work with, but you are hitting the limits of their willingness to understand your subjective experience.

Metaphors of imagery

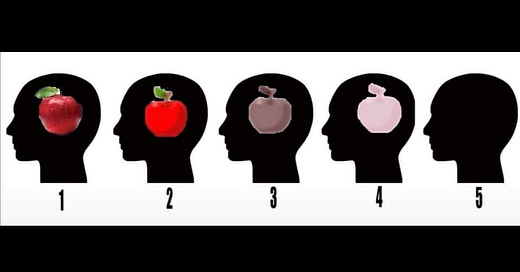

I “have aphantasia” (scare quotes because I increasingly think this is a fake category, and that treating it as intrinsic is not helpful for understanding the experience), in the sense that I have no to minimal ability to visualise things.

A common experience of people who can’t visualise is that we hear all this talk of visualising and assume it’s some sort of metaphor for more general imaginative processes. Then at some point, usually quite late in life (it was in my 20s for me, although I remember conversations from much earlier that should have clued me in where I just went “Huh. Weird.”), they have a record scratch moment where they realise that no, people are being literal, they really can form pictures in their head.

But actually no it turns out we were right the first time. It is a metaphor. It’s just that it’s a very good metaphor for an experience that we lack, and that people who have it are bad at explaining which bits are literal and which bits are metaphorical, because people are bad at explaining things and this is a particularly hard thing to explain.

The thing that helped me understand this is the chapter “Galton’s Other Folly” from Eric Schwitzgebel’s book “Perplexities of Consciousness”, and in particular the following section:

Close your eyes and form a visual image. (Are your eyes closed? No, I can tell, you’re peeking!) Imagine — as Galton (1880) suggests in his first classic study of imagery, which I will discuss in more detail shortly — your breakfast table as you sat down to it this morning. Or imagine the front of your house as viewed from the street. Assuming that you can form such imagery(some people say they can’t), consider this: How well do you know, right now, that imagery experience? You know, I assume, that you have an image, and you know some aspects of its content — that it is your house, say, from a particular point of view. But that really isn ’ t to say very much about your imagery experience.

Consider these further questions: How much of the scene can you vividly visualize at once? Can you keep the image of the chimney vividly in mind at the same time that you vividly imagine your front door, or does the image of the chimney fade as you begin to think about the door? How much detail does your image have? How stable is it? If you can’t visually imagine the entire front of your house in rich detail all at once, what happens to the aspects of the image that are relatively less detailed? If the chimney is still experienced as part of your imagery when your imagemaking energies are focused on the front door, how exactly is it experienced?

Does it have determinate shape, determinate color? In general, do the objects in your image have color before you think to assign color to them, or do some of the colors remain indeterminate, at least for a while (as, in chapter 1, I suggested may be the case for many dream objects)? If there is indeterminacy of color, how is that indeterminacy experienced? As gray? Does your visual image have depth in the same way your sensory visual experience does ( if it does — see chapter 2), or is your imagery somehow flatter, more like a sketch or a picture? How much is your visual imagery like the experience of seeing a picture, or having phosphenes (the spots of color many people report when they press on their eyes 2 ), or afterimages, or dreams, or daydreams? Do you experience the image as located somewhere in egocentric space — inside your head, or before your eyes, or in front of your forehead — or does it make no sense to attempt to assign it a position in this way?

Most of the people I have interviewed about their imagery, when faced with such a series of questions, stumble or feel uncertain at some point. The questions seem hard — at least some of them do (different ones, I’ve found, to different people). They seem like questions one might get wrong, even when reflecting calmly and patiently.

Schwitzgebel is using this to make a general point about people’s fallibility when reporting subjective experience, but I would like to focus on the more specific point: If visualisation worked like people say it does, and people could just call up pictures in their head, this wouldn’t be hard.

When people say they can create images in their head, this is no more literal than saying that a pain is stabbing. You’re not literally being stabbed, and they are not literally conjuring an image, but “conjuring an image” is the best metaphor available to them and so that is how they describe it.

Which isn’t to say there is no difference between them and me, because I definitely do not reliably have experiences which would feel natural to explain through metaphors like this, but it helps to understand what the actual experiential difference is.

What is it like to visualise?

Here is something I have said to multiple people who can visualise better than me and they have instantly gone “Yes, exactly that”, so I am pretty confident that this is an accurate description of the experience of visualisation.

People have an inner monologue - a voice in their head that they have some large but not necessarily total degree of control over. You can generate words in your head, in an experience that is very similar to that of speaking out loud, but that is easily distinguishable from speaking out loud. “Oh did I say that out loud?” is mostly a joke precisely because it is very hard to confuse the experience of saying something in your head from saying it out loud4.

When you are using your inner monologue, you are producing something in your head that is like sound, but also is clearly not sound. It has many of the same characteristics as sound, but you are generally at no risk of confusing the two. It is “as if” you are generating that sound (and sometimes as if that sound is being generated outside your control), but it is in some sense very clearly inside your head and not a real sound and differs from the experience of hearing a real sound in crucial ways.

Anyway, visualisation is like that. You are not literally seeing an image, in the same way that you are not literally hearing a sound when you are using your inner monologue, but what you are doing is like seeing an image in the same way that using your inner monologue is like hearing a sound. You are doing something where the closest analogy in the shared world is literally looking at a thing, but it would be very hard to actually confuse the two experiences.

This is, of course, not entirely helpful in that it is reducing one internal experience to another, and we now have to describe that internal experience. But fortunately I actually do have an inner monologue, so I am better at describing that.

What is it like to have an inner monologue?

Firstly, I’d like to note that there are at least three distinct experiences that people mean when they say “inner monologue”. People sometimes say they don’t have an inner monologue, but as far as I can tell they mean only one of these things and it’s not a thing that many people have.

The first which I will take to be the central example of an inner monologue is that you can generate something like the experience of speaking, but entirely silently in your head. People who I have talked to who say they don’t have an inner monologue generally still say they can do this but it’s effortful, it’s not the default. This is as far as I can tell normal, although presumably the amount of effort required varies.

I can well believe that there are people who can’t do this, but I have not talked to them if so and I don’t know what their experience is like.

The thing that some people have and most people don’t is what you might call internal narration. You are literally thinking most of your life in words. When you wander over to make a cup of tea you are literally generating words in your head along the lines of “OK, I need some tea, so first I need to boil the kettle and get a mug out oh the mugs are all in the dishwasher but it’s clean so let me get one out of there and I can put the rest away afterwards and…”. It is an internal experience in which you are actively describing your ongoing experience as words.

This is not a metaphor, this is genuinely how some people actually use their inner monologue. As far as I can tell based purely on anecdata, doing this is primarily an ADHD thing - some combination of symptom and coping strategy, they are using the internal narration to keep on track. I definitely sometimes do this when I’m having a particularly tired and poor focus day, and it’s a useful strategy for that, although it’s even better if you do it out loud because then you can take advantage of echoic memory as a supplement to your working memory, which does not generally work with your inner monologue.

Anyway, most people who say they lack an inner monologue seem to be taking internal narration as the central example of an inner monologue, but it’s not. Most people don’t do that, and the default experience is that you can act without verbally thinking through your actions, and that indeed most actions are like that.

In the other direction, there is another subjectively distinct thing that one might call an inner monologue, which is not generating coherent speech but instead feels like more like listening to a chaotic jumble of words just at the edge of your hearing. It’s like being in the middle of a storm of word fragments. Like you’re sitting in a crowd of people talking in low conversation and it mostly comes out as white noise but every now and then a fragment of words - sometimes discernible, sometimes only as the impression that there was a word there if you could just hear it - comes through to you.

I want to be clear, this is a metaphor, it is no more literal than the inner monologue is literal hearing.

It’s not always like this - sometimes it’s a bit louder but still not a coherent stream of words. It’s like listening to someone who is clearly thinking faster than they’re speaking and as a result stops midway or changes direction. Or someone who is babbling semi-incoherently but the sense of their meaning becomes clear.

Except, of course, all of this is internal, so there is an available mental motion to bring the thoughts you hear the edge of more into focus if you want it to be.

Let’s call this sort of “inner monologue” instead “mental muttering”. It’s clearly verbal, but it’s a verbal byproduct of other thinking rather than intentional inner monologue, and it doesn’t have the deliberateness of a true monologue.

I first noticed this monologue/muttering split when trying to understand the subjective experience of reading. I speed read, more or less always have, and have always experienced this as quite verbal - one is after all trying to take in words, right? All of the advice on speed reading says that you should not vocalise what you’re reading, because it slows you down, and I was confused as to why that was my experience.

When talking to people about this (as it happens on a Google internal mailing list), the mental muttering / inner monologue distinction became clear, because what I experience when reading is definitely not inner monologue, but instead mental muttering. The words I’m reading come to me all out of order, and often skipped, jumping back and forth around the paragraph I’m on. It’s more like some mental subprocess is consuming the text and I’m hearing its muttering as it reads than it is that I’m literally hearing the words of the text in my inner monologue. I can do the latter, but it’s very effortful and clearly much slower than my normal reading process - I’d generally rather read out loud than fully vocalise reading in my head.

I’ve noticed this with other auditory imagination too. I can e.g. play music in my head,5 and I notice the same patterns of muscle tension that I would with using my inner monologue as well, even when it’s music I could never recreate vocally (even if I were able to sing well).

How do you monologue?

Part of why I am interested in this distinction is that it feels like I have the visualisation equivalent of mental muttering but not the visualisation equivalent of inner monologue. If I try to, for example, close my eyes and think about what my favourite mug looks like, I can describe the mug to you but I do not see a picture of it in front of my eyes. What I do experience is a sort of… flickering impression of quasi-visual stuff. The sense that there is an image there that I am not seeing, and something that is almost but not quite entirely unlike seeing flashes of bits of that image.

This, naturally, lead me to wonder how the transition from mental muttering to inner monologue works. What is the thing that allows me to do deliberate inner monologue, and how does it differ from mental muttering?

It turns out the answer is almost embarrassingly simple. I don’t know how universal this experience is (reports have been mixed, although I’m not 100% certain that the people who said they haven’t noticed it aren’t just missing something subtle, but it’s certainly not just me): When I am producing inner monologue, I am literally engaging the muscles I would use for speaking. It’s not full subvocalisation, but there is a sort of tightening at the back of my tongue and some movement in my throat that feels like the beginnings of speech. It seems to be almost impossible for me to voluntarily produce full inner monologue without that movement.

My hunch is that failures to visualise are partly due to lacking some key insight of this nature. Like there is literally just something you’re not thinking to do, and there is just some trick we are missing.

In aid of figuring out what the trick was, I asked on Twitter:

Based on this, I think the answer is this: At least for me, when I was trying to visualise I would close my eyes and go internal, essentially unfocusing my eyes even though they were closed. In contrast, if I try to keep my eyes focused (but still closed), on the object I am trying to visualise, my attempts to visualise are much more successful in slightly hard to define ways. It’s not that I now can visualise and I see an image there, but the experience feels in some indefinable way much more coherent than my previous unfocused attempts.

Additionally, when sharing a draft of this post with discord I discovered that in fact many people prefer to visualise with their eyes open. I have literally no idea how that is supposed to work (I assume it works the same as how I can make an inner monologue when I’m also hearing things, but the experience feels entirely inaccessible to me). I did some polling on Twitter to see and yup this is a common thing:

An image too dark to see, clearly seen

After I figured out the eye focusing trick, I combined this with another theory of mine about what visualisation is doing and produced something that feels like one of the more coherent visualisation-adjacent experiences I can reliably produce.

My other theory is this: I think visualisation is almost entirely a layer on top of what’s actually going on. What people think they are doing through visualisation is, I suspect, usually some underlying capability which they are then introspecting visually (this is also how I think verbalisation works - a dedicated capability for speech that is mostly accessing information and capabilities represented nonverbally). The visualisation certainly isn’t useless, in that it gives you a good representation for accessing the capability and interacting with it better, but it’s not essential either.

I’ve thought this for a while, as people keep asking me how I do things that they think of visualisation as essential for, and reliably my answer is something along the lines of “I just… do? I make the mental motion for my brain to do the thing and my brain does the thing and gives me the answer. What would I use the picture for?”6

On top of this, the research (as cited by Schwitzgebel in “Galton’s Other Folly”. I haven’t done a careful read of it) seems to back me up on this. The link between self-report of visualisation ability and performance on tests of skills that people say they use visualisation for seems to be extremely weak.

This lead me to the idea of trying to layer visualisation on top of something else rather than free form visualise, and there was an obvious candidate for this: Proprioception.

So, here’s an exercise: Close your eyes, hold your hands out in front of you, and focus your eyes (through your closed lids) on where your hands are, and try to hold in your mind a concept of what they would look like. Move them around in various ways, and try to keep that concept up to date, while maintaining your “visual” focus on them.

For me at least this results in something that feels quite like “seeing”, despite an absence of visual imagery. The best I can describe it is as like looking at something through a thick, dark, fog, or like I’m looking at it through thick black glass, and yet it is still clearly defined at the bits I’m focusing on. An image too dark to see, clearly seen.

It’s not unlike what you would see if your eyes were closed but something moved between you and a bright light (I’ve tested and it’s not literally this - it’s repeatable in the dark with a blindfold and also I can seemingly do this even if I move my hand outside of my actual field of vision. My eyes seem to just need to focus on something rather than the actual position of my hand), except with more clearly defined edges.

I can even extend this a bit to visualising objects I’m holding. e.g. if I close my eyes and pick up and move my laptop about right now, I can still “see” it in the same sort of not-quite-seeing way that I would my hand.

To some extent I can even extend this to objects I’m not holding. After a while practicing this, I’ve noticed that if I close my eyes I can maintain a sort of visual echo of my surroundings that looks much like the above.

(It doesn’t maintain accuracy all that well. I’ve tried do this while walking around and the position of objects very much drifts. This is more evidence that I’m not seeing things through my eyelids, but also means I have to rely on dead reckoning and echolocation to not walk into things. I do not appear to be able to easily layer this “visualisation” on top of dead reckoning and echolocation… yet).

What is it like to dream?

Historically, dreams for me have had very little in the way of visual content. They’ve felt more like an abstract sequence of events that I am aware of happening than they have like something I am actually present in. There’s some physical sensation, some… I guess it’s sound, but it’s much closer to the idea of sound. e.g. I can have conversations in dreams and I think the experience is much closer to the nonlinear experience of reading than it is to listening to someone say literal words.

One of the things I’ve been noticing as I experiment with visualisation is that my dreams have become somewhat more visual. There’s still nothing in the way of full visual imagery in them, but there are more flashes of imagery, and recently there have even been a few states that might be something like semi-lucid dreaming as I fall asleep, where my ability to generate visual imagery somehow comes online as I’m falling asleep.

The result is not some sort of fully controllable ability to visualise. It’s more like my brain is free associating random visuals and I’m just watching the show, although I do have some ability to influence it (it feels very like the sort of steering one can apply to mental muttering). They tend towards abstract, blurry, patterns or representations. Sometimes they’re memories, especially of people I know.

In general it feels very drifty, for want of a better word. I am, literally, dozing and half-aware of something that’s going on.

A more intense version of this comes up when I’m running a high fever. This tends to cause some of the most vivid dreams I experience, and those definitely have a visual component to them. Feverish experiences for me tend to be loud, chaotic, and somewhat uncontrolled. It’s more like the volume of the mental muttering has been turned up on all of the senses. It certainly doesn’t feel like an imaginative process under my control, but it does feel like I’m getting access to bits of the imaginative experience that are normally walled off, and that’s interesting.

What’s next?

This isn’t a very active project for me and so I’m just chipping away at bits of it as I remember and notice things. Being able to visualise sounds interesting, but it’s not a very high priority for me.

I feel like there are some obvious next steps to pursue such as e.g.

Continuing the practice of trying to generate “visual echoes” where I close my eyes and try to picture what I just saw.

See if I can do anything like it with my eyes open but unfocused.

Actually do the image streaming exercises.

Learn to draw, which would likely improve my ability to relate to visuals instead.

Work on sense memory by trying to recall objects in increasingly fine detail.

All of these are very much variants on the theme of applying the fully general system to the problem of visualisation - starting from things I can do and expanding outwards. It’s very unclear whether that’s the right approach - it will certainly do something interesting, but it won’t necessarily get me to visualisation.

It might be that I’m missing some deep trick and that the thing I need to actually do is take some acid (that would be illegal of course, so I won’t) or a couple thousand hours of meditation or something.

It might also be that aphantasia is a fully innate and immutable characteristic of brains and there’s nothing I can do to fix this. I’m sceptical of this, both because it sounds fake and because some people do report successful changes in their ability to visualise, but it certainly could be true.

Anyway I don’t plan to do any of this. My current plans are instead just to vaguely chip away at the edges, paying attention to the subjective experience of imagination as usual, and see if anything interesting comes up, because none of this is my top priority right now. But if it’s something you want to work on yourself, do get in touch and I’ll happily answer questions and help you plan!

Postscript

Share the news!

If you liked this issue, you are welcome and encouraged to forward it to your friends, or share it on your favourite social media site:

If you’re one of those friends it’s been forwarded to or shared with and are reading this, I hope you enjoyed it, and encourage you to subscribe to get more of it!

Consulting

My day job isn’t actually helping people visualise, but it does involve explaining things clearly that other people are struggling to understand. Which is to say I do consulting - I come in to companies, talk to people, and help them understand their problems better and come up with ways to tackle them. If that sounds appealing, you should get in touch. My expertise is primarily with software companies, but I’m happy to talk to people in other industries too.

You can find out more on my consulting site, or just book a free intro call to chat about your company’s problems and get a bit of free consulting on them to discover if we’re a good fit.

(Seriously, book the calls. They’re free and usually extremely helpful to people)

In addition, if you’re a software developer I offer open-enrolment group coaching sessions every Friday morning UK time. This is an opportunity to talk about the challenges you face at work with me and up to three other developers. It’s a mix of me providing coaching and moderating discussion between you all, allowing you to get a wide variety of perspectives and a more affordable version of my one-on-one coaching practice. You can sign up for these group coaching sessions here.

Community

If you’d like to hang out with the sort of people who read this sort of piece, you can join us in the Overthinking Everything discord by clicking this invitation link. You can also read more about it in our community guide first if you like.

Which, of course, we might not if one of us is red-green colour blind!

I do know one person who claims never to have a headache. When he told me this I gave myself a headache trying to set him on fire with my mind.

It seems to be a caffeine withdrawal symptom, or at least I get it much less when I don’t have a regular caffeine habit.

Saying things involuntarily or inadvertently absolutely does happen, but it doesn’t seem to be much like “I meant to say that in my head and I said it out loud”.

Oddly, 100% of the time I test this the tune that comes to mind is Fur Elise. I think because I spent a lot of time learning to play it on the piano as a kid.

Sometimes I use a kinaesthetic representation instead, so it does feel like there is a literal motion attached.