If you're stuck, try something different

Hi everyone,

I’ve been blocked on writing a newsletter so far this month for stupid reasons (I have a draft that was supposed to be easy to write and starts “Welcome to August” and is still unfinished two weeks in), so here’s something different.

By coincidence, I’m going to be telling you about a totally different context in which this advice also applies, which is when you’re trying to get better at a skill and have reached a point where you don’t know how to proceed.

What’s the problem?

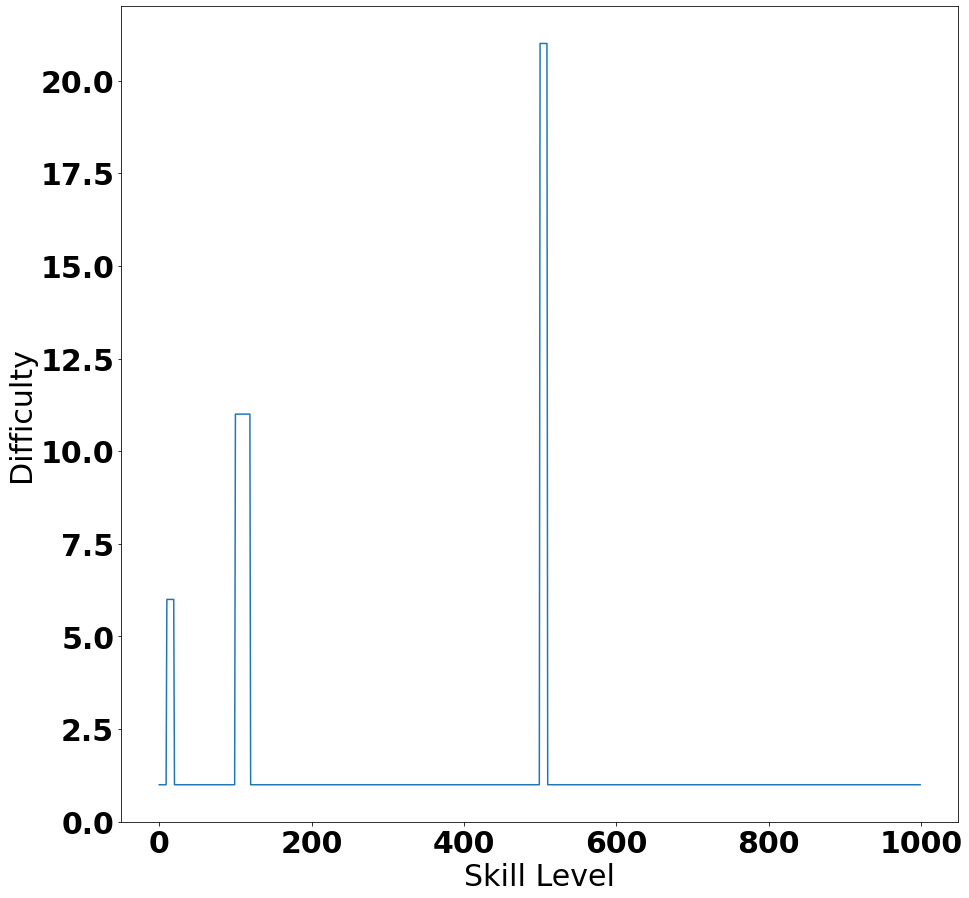

In Clearing hurdles in learning I suggested that the difficulty of improving your skill level often takes the following form:

That is, it’s normally quite easy to get better, but sometimes you hit periods where there is some hurdle to overcome and it briefly becomes much harder to improve.

Part of why I’m interested in this is that I think often people need help overcoming these hurdles: They frequently correspond to bugs in your understanding of the skill (cf. Errors vs. Bugs and the End of Stupidity), or habits that you need to break out of, that a skilled teacher can help you break out of.

But what do you do if you’re learning on your own? e.g. it’s something weirdly specific that doesn’t really have anything in the way of formal instruction, or finding a teacher for it is too hard, or one of any other number of reasons why you might not have or want a teacher.

A fairly general strategy for how to overcome these hurdles is to make what I would call a lateral move - instead of trying to keep moving upwards, move sideways, and switch away from learning the thing you’re stuck on to something related to it, then come back and see if you’re still stuck.

This can work for a number of different reasons, but I’m only going to cover one of them in this piece.

Lateral moves create new skills

This newsletter issue is inspired by my friend Cedric, in two capacities. The first is a recent thread he had about how learning from doing works:

One of the things he talks about in this is that in order to learn you have to destroy wrong mental models:

To which I replied that it’s not so much that you have to destroy them as you have to learn to see them as not relevant in context:

This seems like a thing that comes up in learning a great deal, and I suspect is often the reason why we get stuck: It’s not just that learning to improve is hard, but that we need to simultaneously learn how to improve and learn how to not do the thing we’re already habitually doing.

But this leads to a problem. There are two parts of replacing a skill you’ve learned wrong with a corrected version: You have to stop using the old version, and you have to build a new version to replace it.

If building the new skill is easy this isn’t necessarily a problem, but if you’re trying to learn to do something hard while also fighting your habits telling you to do things the easy way, you’re going to have a bad time.

If, in contrast, you can change the situation up enough that your habits no longer apply, you can build the new skill separately from unlearning the old skill. Now when you are learning to replace the old skill, you have the skill you need more or less ready to drop in place.

This brings us to the other reason Cedric has inspired this piece, which is that he was complaining to me recently that he couldn’t use chopsticks properly. He was self-taught1, and as a result although he can use them adequately for normal purposes, he struggles with tricky chopstick tasks, and his existing habits make it very hard for him to learn to use them properly.

Naturally, as a white man, I was all too happy to tell my Asian friend all about how chopsticks should work and why he was using them wrong.

Uh. That is to say, I use chopsticks wrong too, but I suggested that if he wanted to get better at them, he should try learning to use cooking chopsticks2 properly, because cooking chopsticks are different enough from regular chopsticks to break him out of his habits, he could learn to use them the right way, and then try to transfer that learning back.3

I don’t know if this is going to work, but it’s intuitively plausible to me that it would. Cooking chopsticks are different enough (and harder) that they should break him out of his pre-existing habits and give him a chance to learn properly. We’ll see if it works.

A similar principle is that I’ve been talking to people about touch typing recently and I think it’s pretty common to touch type “improperly” (I probably do, although I think I’m pretty close to right), and some people report that in the long run this can cause problems with RSI (I haven’t investigated this claim much). How would one go about learning to touch type properly starting from improperly? Well, maybe try doing it on a DVORAK keyboard layout instead of QWERTY?

Related Reading

I’m not sure I’ve ever quite so explicitly codified this strategy, but it comes up over and over again in my work. Here are a few other examples.

This came up recently in Unlearning, where I discussed how often the problem we have with improving our skills is not that we don’t know how to do something, but that we do know how to do something and it’s wrong, and we first need to unlearn those habits. I cited an example from “How Children Fail”, where children who learned mathematics to the exam often ended up not just having learned it badly, but incorrectly - they had a wrong mental model of how to do mathematics, which they had to replace with a right one, and this was harder than learning the right model in the first place.

More recently how to write like this is about learning to write in different voices for nonfiction, prompted by my recent You have to do the easy bits first, which was written in a more poetic style. I suggested that the easiest way to learn such styles was to do write exercises where you explicitly limited the form you wrote in but didn’t otherwise make an attempt to change your voice.

A different reason I’ve proposed lateral moves as useful (which I think is also true) in the past is Constraints on skill growth, in which I proposed slightly larger lateral moves than this (e.g. moving from mathematics to programming or vice versa), because they let you get good at subskills that are hard to practice in the broader skill.

Remastery training is an example of this which I wrote about (and also an example of changing the writing tone), in which you get good at Slay the Spire by starting the game from scratch and making it hard in a particular way that you’re struggling with at the top level, which is a similar example of a lateral move.

And of course, my foundational post for a lot of this is How to do hard things, which is the basis of the idea there: You find something easy, and you make it hard in a way that you’re struggling with in the general skill. This isn’t really an example of a lateral move in general, but it’s often the idea that underlies some of them.

Postscript

Consulting

My day job isn’t actually helping people understand humour, but it does involve helping people understand how to have a better and more productive relationship with their colleagues and their work. Which is to say I do consulting - I come in to companies, talk to people, and help them understand their problems better and come up with ways to tackle them. If that sounds appealing, you should get in touch. My expertise is primarily with software companies, but I’m happy to talk to people in other industries too.

You can find out more on my consulting site, or just book a free intro call to chat about your company’s problems and get a bit of free consulting on them to discover if we’re a good fit.

(Seriously, book the calls. They’re free and usually extremely helpful to people)

Community

If you’d like to hang out with the sort of people who read this sort of piece, you can join us in the Overthinking Everything discord by clicking this invitation link. You can also read more about it in our community guide first if you like.

If you’ll pardon some brief shilling for my business, I still have some availability for one-off coaching sessions, so if you’d like a coaching session with me, you can book a session using Calendly. I’ve also recently started offering Ask Me Anything sessions, which are designed for you to pick my brains on whatever topic you like that you think I could help you with.

Cover image

The cover image for this post (only really visible on the index page and in social media cards) is this picture of a pair of cooking chopsticks, taken by Wikimedia user OttawaAC.

Share the news!

Finally, if you liked this issue, you are welcome and encouraged to forward it to your friends.

If you’re one of those friends it’s been forwarded to and are reading this, I hope you enjoyed it, and encourage you to subscribe to get more of it!

I checked in with him before relaying this story and he says “you may even tell the world that I learnt chopsticks with two pencils and an erasers, and Asian parents everywhere should learn from my experience and not leave their kid to learn chopsticks on their own!”

Cooking chopsticks are like normal chopsticks but stupidly long and typically pointier.

“David, have you even seen cooking chopsticks, they’re ridiculous!” “Be right back” *clacks cooking chopsticks at the video camera*